“It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men of their own choice if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood.”

- James Madison[1]

Interpreting and implementing EHS regulations can be a significant part of an EHS professional’s job, so this section is intended to provide an explanation of the U.S. regulatory framework. Even though this part of EHS is relatively boring, it is a foundational necessity that is often overlooked and misunderstood. The following sections provides an overview of the how regulations are enacted, organized and applied.

3.1 Acts

Congress writes an act that broadly describes what needs to be done to address a safety or environmental issue. Historically, this legislative action follows the occurrence of a major incident or an issue that rises to public attention. Many EHS regulations can be correlated with to a major incident or two, such as:

- Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act Emergency Planning and Community Right-To-Know Act (EPCRA): Union Carbide chemical releases in Bhobal, India, and Institute, West Virginia

- Oil Pollution Act Oil Pollution Act (OPA): Exxon Valdez oil spill

- Process Safety Management Process Safety Management (PSM) and Chemical Accident Prevention Program (CAPP): Phillips 66 Pasadena, Texas fire and explosion

An act typically specifies what regulatory agencies are responsible for implementation. A single act may be delegated to multiple regulatory agencies for implementation, such as the Clean Air Act Clean Air Act (CAA) amendments of 1990, which resulted in the following regulations for two different agencies:

- Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Chemical Accident Prevention Provisions (CAPP), also known as the Risk Management Program or Plan regulation

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)) Process Safety Management Process Safety Management (PSM) of Highly Hazardous Chemicals

Published acts can be found in the United States Code. The acts are divided into 53 titles/subject matters and the EHS-related acts are typically found in Title 42—The Public Health and Welfare[2]. I seldom review or reference EHS acts in my work, but if you have a need for information on these acts, this website may be helpful: Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives.

3.2 Federal Register

The Federal regulatory agencies are designated the responsibility for developing a proposed regulation (i.e., a notice of proposed rulemaking or NPRM), which is published in the Federal Register[3]. The Federal Register is the official publication of the federal government which publishes presidential documents, rules, proposed rules and notices[4]. Sometimes the regulatory agency issues an advance notice of proposed rule (ANPR) to solicit pre-proposal comments. After public comment, the federal regulatory agency promulgates the regulation, which will also be issued in the Federal Register.

In 1994, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed changes to the Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) plan regulation in the Federal register. This was the first time I had read a Federal Register and even though I had conducted many Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) inspections as a consultant for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), I was shocked at how much I learned from reading the preamble to this proposal. The preambles to the actual regulations provide details on the thinking behind the proposed and promulgated regulations and address comments from the regulated community and non-government organizations. Invaluable information can be found in the preambles, including:

- Alternative regulations considered

- Reasoning for accepting certain regulations and denying others

- Responses to comments posed by the public

- Cost analysis

Recently, an example of the importance of Federal Register documents was became evident when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a significant determination on an air permit that was inconsistent with our industry group’s interpretation of the regulation. We were unable to find information that proved our point, however, until one member of our industry group identified the information in the original 1980 Federal Register that proved us correct.

Some links to Federal Register documents include:

- Federal Register website: https://www.federalregister.gov/

- Government Printing Office Federal Register link: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=FR

You can sign up to receive e-mails with Federal Register updates from the Federal Register website.

3.3 Code of Federal Regulations Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)

The final regulations are divided by subject matter into chapters and published in the Code of Federal Regulations once yearly[5]. Pertinent EHS chapters and the update publication deadlines are detailed in the table below[6].

| Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Volume | Title | Update Deadline |

| 29 | Labor | July 1 |

| 30 | Mineral Resources | July 1 |

| 33 | Navigation and Navigable Waters | July 1 |

| 40 | Protection of Environmental | July 1 |

| 46 | Shipping | October 1 |

| 49 | Transportation | October 1 |

| 50 | Wildlife and Fisheries | October 1 |

Within these chapters are subchapters and parts with the specific regulations. I have included some of the specific EHS sections that can impact regulated industries in the table below. This is not an exhaustive list and some industries may be impacted by regulations outside of this list.

| Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Volume | Subject | Regulatory Entity | Parts |

| 29 | Labor | Occupational Safety and Health Administration | 1901 to 1990 |

| 30 | Mineral Resources | Mine Safety and Health Administration | 46 to 104 |

| 33 | Navigation and Navigable Waters | Army Corps of Engineers | 150 to 159 and 320 to 332 |

| 40 | Protection of Environment | Environmental Protection Agency | 1 to 1099 |

| 40 | Protection of Environment | Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Justice | 1400 to 1499 |

| 40 | Protection of Environment | Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board | 1600 to 1699 |

| 46 | Shipping | Coast Guard | 140 to 154 |

| 49 | Transportation | Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration | 100 to 199 |

| 50 | Wildlife and Fisheries | Fish and Wildlife Service | 10 to 24 |

Each volume is divided into chapters, subchapters, subparts and parts. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) (i.e., Title 1 General Provisions) delineates the organization of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) as follows:

1 Titles, numbered consecutively in Arabic

A Subtitles, lettered consecutively in capitals

I Chapters, numbered consecutively in Roman capitals

a Subchapters, lettered consecutively in capitals

1 Parts, numbered in Arabic

A Subparts, lettered in capitals;

1 Sections, numbered in Arabic.

Paragraphs, which are designated as follows:

(a) level 1

(1) level 2

(i) level 3

(A) level 4

(1) level 5

(i) level 6 [7]

A specific regulatory citation can be written out as:

“Title 29—Labor, Subtitle B—Regulations Relating To Labor, Chapter XVII—Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Department Of Labor, Part 1910—Occupational Safety And Health Standards, Subpart D—Walking-Working Surfaces, Part 21 Scope and Definitions.”

A simpler, and common way to write this is to skip the subchapters, and subparts and write it as “29 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 1910.21”, using the silcrow symbol “§” as “29 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) § 1910.21”, or simply 29 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 1910.21.

In the early 1990’s when I worked as a consultant to the EPA, we would hand out copies of the regulations to facilities that we inspected: At the time, the regulated community did not have practical methods for obtaining copies of this information. In order to obtain a copy, it was necessary to locate and travel to the nearest federal depository, read through the Code of Federal Regulations Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and Federal Registers and/or make photocopies of the regulations. The development of the internet now offers easy access to regulations and guidance documents. However, this ready access to regulations has resulted in changed regulatory expectations; it is more difficult to claim ignorance of the law.

When I would visit some large chemical companies, refineries and power plants around the same time, I would admire their color-coded collection of Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)s. Our office would have one copy and I typically used worn out photocopies that were barely readable. Fortunately, that is no longer an issue: you can find numerous website sources for the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) including:

- Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

- GovInfo Code of Federal Regulations (Annual Addition)

- e-Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) website

The GovInfo Code of Federal Regulations website has options for downloading files as Adobe Acrobat, Text and XML, which I find useful for searching, printing and copying the regulation.

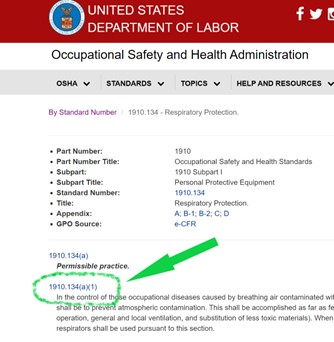

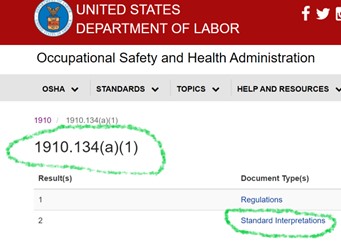

For Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) safety regulations, I often use the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations (Standards – 29 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)) website because it contains links to interpretations. If a regulatory-part text is a hyperlink (i.e., blue-colored text) as shown below, you can click on that link and it will take you to a list of standard interpretations related to that particular regulation.

3.3.1 State and Tribal Regulations

States and Tribes can have their own EHS regulations and regulatory agencies. The EHS regulations may be covered by multiple agencies such as a department of environmental protection, department of environmental quality, department of health, department of labor, department of natural resources, state fire marshal, etc. The regulations, agencies, policies, etc. become more varied and difficult to discuss and explain due to their differences. Therefore, I am not going to try to address this further.

Federal agencies can delegate their programs to states. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires that state programs be at least as effective as the federal program[8]. Some states do not have their own programs. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) delegates their programs to the states to cover either state and local government workers only or private workplaces and state and local government[9]. The state may also choose not to cover certain industry types. For example, South Carolina’s State Plan does not cover maritime employment[10].

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on the other hand, delegates specific programs so a state may have an air permit program, but the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) may run the stormwater program in that state[11].

Other programs, such as the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) plan regulation cannot be delegated to the states: The Clean Water Act does not allow the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to delegate this program[12]. This does not preclude some states from promulgating and running their own similar programs: Several states have their own programs like the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) regulation (e.g., Michigan’s Pollution Incident Prevention Plan regulation)[13].

Where the state is responsible for implementing the federal environmental program, the states’ regulations generally have to be at least as stringent as the federal versions. I have not conducted an exhaustive review to verify that all state-implemented Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations have to be as least as strict, but in my experience, that is the general rule. This is specifically mentioned in the State Implementation Plan (SIP) guidance that discusses how state’s implement Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) air quality regulations[14].

3.3.2 Jurisdiction Issues

Knowing the authority of a regulatory agency is crucial to understanding what EHS regulations apply to your facilities. I am often surprised by how complicated this concept can be with overlapping agency authority, scopes that are dependent on minute details and others that can change from year to year.

The overlap of authority between federal agencies is not always clear, so the jurisdiction is typically spelled out in an agreement or memorandum of understanding (MOU). One example is the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) who both govern safety for the Department of Labor (DOL). The jurisdiction of each is spelled out in Interagency Agreement between the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) that generally assigns responsibilities for mines and associated operations to the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) responsible for the other industries[15]. However, this seemingly simple jurisdiction delineation can be confusing and result in significant controversy. In a recent borrow pit case, the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) assumed authority, even though the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has authority over borrow pits in the Interagency Agreement, because the material pulled from the borrow pit was added to the haul roads for traction and not for fill[16].

The Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) example discussed above was between two agencies in the same department. Jurisdiction can become more complicated when it involves agencies in different departments. The Clean Water Act Clean Water Act (CWA) and Oil Pollution Act Oil Pollution Act (OPA) resulted in several Memorandum Of Understandings (MOU) among the Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of Transportation, and Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency[17]. The Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) and Facility Response Plan (FRP) regulations contain these Memorandum Of Understandings (MOU) and delineate responsibility and show that the agencies have overlapping responsibilities where a facility might need to prepare a response plan for multiple agencies[18].

Other jurisdictional issues revolve around the scope of the regulation. The definition of wetlands and waters of the United States, which has undergone a series of lawsuits and regulatory reform from 2006 through 2022 is an example of the importance of understanding the scope of a regulation[19]. These lawsuits can impact whether a project requires a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) and a water quality certification from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or state environmental agency. In question is not whether traditional navigable waterways (e.g., rivers) are covered by the applicable regulations, but non-navigable, isolated, intrastate ponds[20]. It’s important to note that the federal jurisdictional issue does not preclude state agencies from regulating these waters, which can just add to the confusion.

One final regulatory jurisdiction issue involves fire codes and the Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ). A state fire marshal, city fire department or other regulatory agency with fire code enforcement (i.e., the Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ)) can adopt various fire codes, which are typically sections of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards, International Fire Code or International Building Code sections. The text below from the Maine Fire Marshal shows the various National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) codes and the different editions that have been adopted by the State of Maine:

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1: Fire Prevention Code, 2018 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 10: Standard for Portable Fire Extinguishers, 2007 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 11: Standard for Low, Medium, and High Expansion Foam Systems, 2005 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 12: Standard on Carbon Dioxide Extinguishing Systems, 2008 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 13: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems, 2016 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 13D: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems in One and Two Family Dwellings and Manufactured Homes, 2016 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 13R: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems in Residential Occupancies up to and Including Four Stories in Height, 2016 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 14: Standard for the Installation of Standpipe, Private Hydrants and Hose Systems, 2013 Edition

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 15: Standard for Water Spray Fixed Systems for Fire Protection, 2012 Edition[21]

3.3.3 Regulatory Scope and Applicability

Within a regulation, the scope and applicability can often be found at the beginning of the regulation. However, the devil is in the details such as the term definitions used to define the scope. Well-written and mature regulations (i.e., older regulations that have been updated and improved) contain the definitions needed for proper interpretation and understanding. It is important to use caution when reviewing the individual regulation’s scope, because it is still limited by the applicable regulatory agency’s overall scope.

Within an agency, it is important to know and understand the scope of their regulations. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has regulations that apply to all industries except mining (i.e., horizontal standards like the recordkeeping requirements in 29 Code of Federal Regulations 1904) and separate regulations that apply to specific industries (i.e., vertical standards)[22]. Examples of vertical standards include Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations for agriculture (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1928), construction (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1926), general industry (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1910), longshoring (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1918), marine terminals (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1917), and shipyard employment (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1915). The safety risk is independent of the scope, but the regulatory risk is not, so understanding which regulations apply to your operations can be important. I think the vertical standard scope is somewhat clear when geographic areas separate the covered operations, like marine terminals. However, the scope becomes even muddier for some standards such as when construction activities, subject to 29 Code of Federal Regulations 1926, occur at other covered sites like general industry sites subject to 29 Code of Federal Regulations 1910. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has provided the following guidance on maintenance activities that would fall under the general industry-standard at an industrial site, versus construction activities that would fall under the construction standard:

“Construction work is not limited to new construction, but can include the repair of existing facilities or the replacement of structures and their components. For example, the replacement of one utility pole with a new, identical pole would be maintenance; however, if it were replaced with an improved pole or equipment, it would be considered construction.[23]”

If the activity has the same regulatory requirements, determining which standard applies may not be an issue, but when the requirements vary, this can be confusing: The general industry standard requires fall protection for an unprotected side or edge that is four feet or more above the lower level[24]. However, the construction industry standard requires fall protection for an unprotected side or edge that is six feet or more above the lower level[25].

Another confusing scope issue involves multiple facilities and whether they are combined under EHS regulations or treated separately. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) regulations provide specific guidance on determining how you count multi-establishment facilities, which is dependent on the various North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) codes[26]. Combining facilities for air permitting regulations, referred to as source aggregation, is less clear and has been the subject of a number of lawsuits and guidance documents and the guidance has changed over time[27].

3.3.4 Chemical Lists

Some EHS regulations’ applicability is based on the production, storage, handling or use of specific chemicals and these regulations often contain lists of these chemicals. What can be a source of confusion is the differences in these lists: If a chemical is a hazardous air pollutant, why wouldn’t it also be hazardous to discharge in water? A chemical may be volatile, so it easily evaporates into the air and is regulated by air permit regulations. That same chemical may not be water soluble and if it does get into water, it might evaporate quickly, so it is not covered by water permit regulations.

Each regulation has specific goals, and the lists are geared towards those goals. A chemical may or may not be regulated for a number of reasons including:

- The behavior of the chemical in that environment

- The way the chemical is used in a particular industry

- The quantity of the chemical used

The 1990 Clean Air Act Clean Air Act (CAA) amendments are an interesting example of different chemical lists. The 1990 Clean Air Act amendment resulted in the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Chemical Accident Prevention Program (CAPP) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Process Safety Management Process Safety Management (PSM) standards, both of which were intended to prevent accidental releases of chemicals with the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) responsibility to protect the public and the environment, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) to protect workers [28]. With the same goal, but different responsibilities, each regulation has similar, but not identical lists of covered chemicals and thresholds with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) thresholds typically higher[29]. I understand the logic behind the differences since it takes more or a chemical to cause an off-site impact to the public and the environment versus an on-site employee. I would expect the same logic to apply to the chemical mobility: gaseous and volatile chemicals are more likely to migrate off the facility property and impact the public and the environment.

Because there are so many EHS chemical lists, I cannot list all of them here. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has consolidated their lists into a searchable database called Substance Registry Services (SRS), which is a great tool for evaluating chemicals to determine what regulations may apply to their storage, production and/or use. The Department of Transportation’s (Department of Transportation (DOT)) hazardous materials list (49 Code of Federal Regulations 172.101) is an important list for EHS professionals as well as Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Limits for Air Contaminants (29 Code of Federal Regulations 1910.1000 Tables Z1, Z2 and Z3).

3.3.5 Regulatory Changes

One challenging part of EHS work is keeping up with new and changing regulations. This is one of the requirements of an environmental health and safety management system.

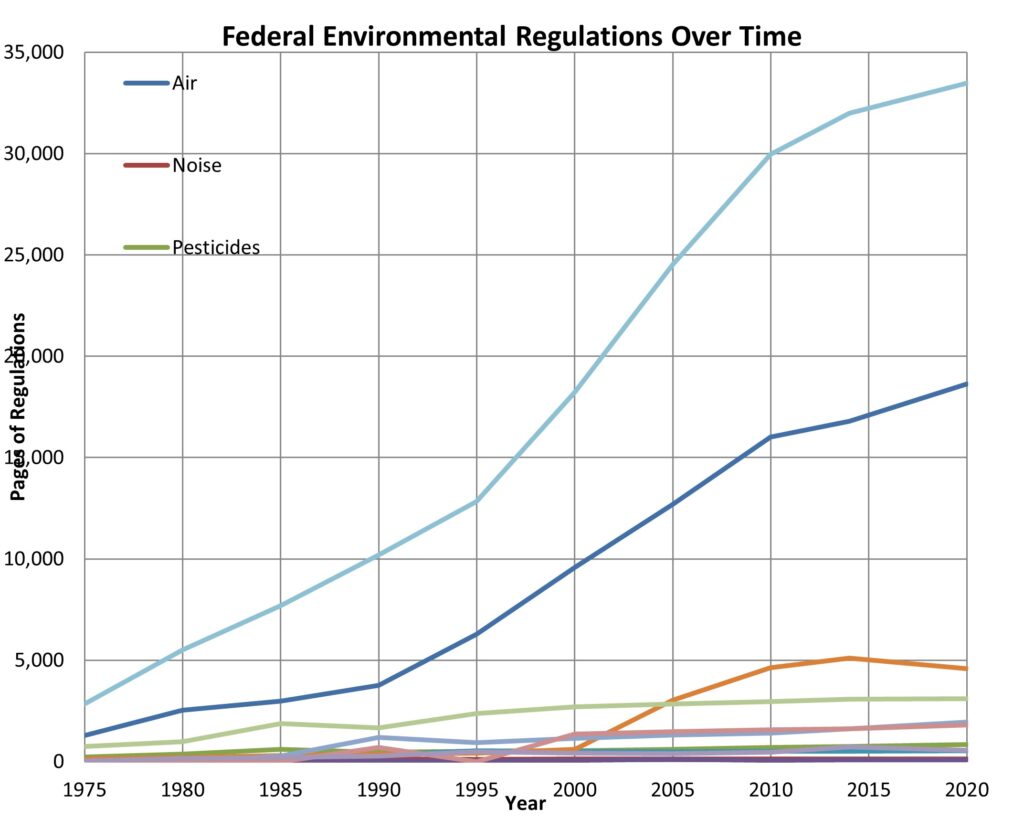

During election campaigns, I often hear about tax reform and the excessive number of tax regulations (e.g., the number of pages of regulations). Following this vane, I compiled the number of pages of environmental regulations. The following chart illustrates the rapid growth of the environmental regulations.

Fortunately, there are a number of ways to stay on top of these regulations including:

- Membership and/or participation in industry groups

- Commercially available regulatory update services

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)[30] and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)[31] list serves

- Web-service alerts

3.4 Interpretations and Guidance

Regulations do not always make sense, especially environmental regulations, which are often less tangible. I have used this mantra in numerous conversations: “Do not try to make sense of the regulations” when non-EHS personnel voice confusion over some requirement that we have to implement. Since the EHS regulations are not always clear, regulatory agencies provide clarification in published interpretations or guidance documents. EHS regulatory agencies can develop interpretations and guidance without going through the rule-making process[32]. It is easy to assume that the interpretations and guidance are required, and a regulatory inspector may look to enforce these items. However, the Administrative Conference of the United States has provided a recommendation (Recommendation 2017-5) to regulatory agencies advising:

“…agencies not to treat policy statements as binding on the public and to take steps to make clear to the public that policy statements are nonbinding.”[33]

Ironically, this is a recommendation (i.e., interpretation and guidance) that also does not have the rule of law. Therefore, it is not advisable to ignore the interpretations and guidance.

When uncertain of a regulatory requirement, a colleague of mine and I fall back on the intent of the regulation and ask if the interpretation or method of implementation meets the intent even if it does not match the guidance. Discussing the interpretation with the regulatory agency is another option, but if you are uncomfortable contacting them directly, you can ask a consultant to make a blind phone call for you to the regulatory agency. However, if the issue could be significant (e.g., a major regulatory violation or significant cost), you may want to discuss it with legal counsel.

Another issue with interpretations and guidance is they are subject to change without notice since they do not go through the rulemaking process. A significant example of this is Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) change in its Process Safety Management Process Safety Management (PSM) retail exemption. On July 22, 2015, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) revised this interpretation to state that retailers are not exempt if they are in certain North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) codes[34]. Overnight, retail facilities storing anhydrous ammonia were subject to the Process Safety Management Process Safety Management (PSM) standard. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) delayed enforcement of the standard for one year to give facilities a chance to develop the Process Safety Management Process Safety Management (PSM) program[35].

Some older interpretations are available so you can justify why you may have taken a certain regulatory position. However, I do not know of a system or method to identify, or be notified, when an interpretation changes. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) identifies older interpretations as “Archived” and provides the following caveat:

“NOTICE: This is an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Archive Document, and may no longer represent Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Policy. It is presented here as historical content, for research and review purposes only.”

For some interpretations, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) will also reference the newer interpretation that replaced the older interpretation.

3.5 For Additional Information

- “About the Code of Federal Regulations” National Archives website (https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/cfr/about.html) accessed December 24, 2020.

- “United States Federal Government Resources: U.S. Federal Regulations” University of Washington, University Libraries website (https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/federal/federal-regulations#:~:text=Regulations%20are%20the%20means%20by%20which%20Federal%20agencies,known%20as%20%22rulemaking.%22%20Regulations%20effect%20our%20everyday%20life%21) accessed July 29, 2022.

3.6 References

[1] Brainy Quotes website (https://www.brainyquote.com/topics/laws-quotes)

[2] “United States Code” Govinfo website (https://www.govinfo.gov/help/uscode) access January 9, 2021

[3] “Federal Register 101” by Amy Bunk, Director of Legal Affairs and Policy, Office of the Federal Register, United States Coast Guard Proceedings (https://uploads.federalregister.gov/uploads/2011/01/fr_101.pdf), Spring 2010, page 56

[4] “Federal Register 101” by Amy Bunk, Director of Legal Affairs and Policy, Office of the Federal Register, United States Coast Guard Proceedings (https://uploads.federalregister.gov/uploads/2011/01/fr_101.pdf), Spring 2010, page 56

[5] “About the Code of Federal Regulations” National Archives website (https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/cfr/about.html) accessed December 24, 2020.

[6] “About the Code of Federal Regulations” National Archives website (https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/cfr/about.html) accessed December 24, 2020.

[7] Title 1 Code of Federal Regulations Section 21.11 Standard Organization of the Code of Federal Regulations

[8] “State Plans/State Plan Frequently Asked Questions” (https://www.osha.gov/stateplans/faqs), accessed December 29, 2020

[9] “State Plans” Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Website (https://www.osha.gov/stateplans) accessed December 29, 2020

[10] “State Plans/South Carolina” Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Website (https://www.osha.gov/stateplans/sc), accessed December 29, 2020

[11] “Authorization Status for EPA’s Construction and Industrial Stormwater Programs“ EPA website (https://www.epa.gov/npdes/authorization-status-epas-construction-and-industrial-stormwater-programs) accessed December 29, 2020

[12] “Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) Guidance for Regional Inspectors” (EPA 550-B-13-001) United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Emergency Management, Regulation and Policy Development Division, Washington, DC, December 16, 2013, Page 2-1

[13] “Michigan’s Part 5 Rules (Spillage of Oil and Polluting Materials) and Pollution Incident Prevention Plans“ website (https://www.michigan.gov/egle/0,9429,7-135-3313_23420—,00.html accessed December 29, 2020

[14] “Basic Information about Air Quality SIPs” EPA website (https://www.epa.gov/sips/basic-information-air-quality-sips) access December 29, 2020

[15] “Interagency Agreement between the Mine Safety and Health Administration U.S. Department of Labor and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration U.S. Department of Labor” Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Website (https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/mou/1979-03-29) accessed January 1, 2021

[16] “Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) Has Upper Hand in Jurisdictional Battle With Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)” (https://jordanramis.com/resources/articles/Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA)-has-upper-hand-in-jurisdictional-battle-with-osha/view/) by Katie Jeremiah, Jordan Ramis PC, Summer 2012

[17] 40 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 112 Appendix A Memorandum of Understanding Between the Secretary of Transportation and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and Appendix B Memorandum of Understanding Among the Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of Transportation, and Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency

[18] “Facility Response Planning Compliance Assistance Guide” (EPA 540-K-02-003d) United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Emergency and Remedial Response, Washington, DC, August 2002, Page 12

[19] “About Waters of the United States” United States Environmental Protection Agency Website (https://www.epa.gov/nwpr/about-waters-united-states#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWaters%20of%20the%20United%20States%E2%80%9D%20is%20a%20threshold,the%20scope%20of%20federal%20jurisdiction%20under%20the%20Act.) Accessed January 1, 2021.

[20] “About Waters of the United States” United States Environmental Protection Agency Website (https://www.epa.gov/nwpr/about-waters-united-states#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWaters%20of%20the%20United%20States%E2%80%9D%20is%20a%20threshold,the%20scope%20of%20federal%20jurisdiction%20under%20the%20Act.) Accessed January 1, 2021.

[21] “State Adopted National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standards”, Office of State Fire Marshal, Department of Public Safety, State of Maine (https://www.maine.gov/dps/fmo/fire-service-laws/nfpa), Accessed October 28, 2021.

[22] “According To Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), What Is The Difference Between Vertical & Horizontal Standards?” LegalBeagle website (According to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), What Is the Difference Between Vertical & Horizontal Standards? (legalbeagle.com)) accessed January 16, 2021.

[23] Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Letter to Mr. Raymond V. Knobbs, Minnotte Contracting Corporation, dated November 18, 2003 (Clarification of maintenance vs. construction activities; standards applicable to the removal and replacement of steel tanks and structural steel supports. | Occupational Safety and Health Administration (osha.gov))

[24] 29 Code of Federal Regulations 1910.28(b)(1)(i)

[25] 29 Code of Federal Regulations 1926.501(b)(1)

[26] “Reporting Forms and Instructions – B.2 Primary North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) Code Determination” EPA website (https://ofmpub.epa.gov/apex/guideme_ext/f?p=guideme:rfi:::::rfi:2_2), Section B.2.b. Multi-establishment Facilities accessed January 18, 2021.

[27] “Source Aggregation: When Are Multiple Facilities Considered One by EPA?” Ryley Carlock & Applewhite, The Business of Solutions website (https://www.rcalaw.com/source-aggregation-when-are-multiple-facilities-considered-one-by-epa) dated April 1, 2015.

[28] “Strategy for Coordinated EPA/Occupational Safety and Health Administration (Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)) Implementation of the Chemical Accident Prevention Requirements of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990” EPA Website (https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2013-10/documents/oshaepa.pdf), accessed February 15, 2021.

[29] Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Process Safety Management (PSM) – A Brief Overview Of Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Process Safety Management (PSM) And How It Correlates To EPA’s Risk Management Program, EPA Website presentation (https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/region_7_osha_psm_and_epa_rmp_program_3.pdf) accessed February 15, 2021

[30] “Email Subscriptions for EPA News Releases, Environmental Protection Agency website (https://www.epa.gov/newsroom/email-subscriptions-epa-news-releases) accessed November 7, 2021

[31] “Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Quicktakes” website (https://www.osha.gov/quicktakes/#subscribe) accessed November 7, 2021

[32] U.S. Code Title 5, part I chapter 5 subchapter II § 553(b)(A)

[33] “Agency Guidance Through Interpretive Rules” Administrative Conference of the United States website accessed November 12, 2021 (https://www.acus.gov/recommendation/agency-guidance-through-interpretive-rules#:~:text=%20Agency%20Guidance%20Through%20Interpretive%20Rules%20%201,agency%2C%20as%20an%20internal%20agency%20management…%20More%20)

[34] “Process Safety Management (PSM) Retail Exemption Interim Enforcement Policy” Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) website accessed November 13, 2021 (https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2015-10-20)

[35] “Process Safety Management (PSM) Retail Exemption Interim Enforcement Policy” Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) website accessed November 13, 2021 (https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2015-10-20)

I am always open to comments and suggestions. You can contact me using the form below.